I Have a Fixed-Rate Mortgage! Why Did My Payment Increase?

Research consistently reveals that mortgage applicants who understand the process through which their Mortgage Loan Originator (MLO) guides them are measurably happier than those who simply go along with the MLO for the ride. Happier customers are more likely to return to that loan originator with future needs and refer others in need of mortgage services.

I began my mortgage-industry career as a Mortgage Customer Service Representative. As a Mortgage Customer Service Representative, I was regularly dumbfounded when customers would call, convinced that we were violating the terms of their mortgage contract, because their payments increased even though their mortgage’s interest rate was fixed. And every time I hung up the phone, after explaining why this happened to each customer’s satisfaction, I felt the pangs of frustration wondering why their mortgage loan originator neglected to explain this to them during their application process.

Of course, if a borrower’s mortgage contains an adjustable interest rate, then his or her payment will fluctuate whenever his or her loan’s interest rate adjusts. But mortgage payments will also fluctuate due to another reason … the escrow account.

The portion of one’s mortgage payment that amortizes the mortgage itself is referred to as the principal and interest (P&I) payment. When a mortgage contains a fixed interest rate, this P&I payment remains constant throughout the loan’s life. Mortgage payments, however, are frequently comprised of more than just a P&I payment. Borrowers’ mortgages often contain an escrow account through which the mortgage servicer remits payments to the borrower’s real estate tax authority and insurance company on that borrower’s behalf. The servicer will collect 1/12th of the anticipated annual disbursements, along with the monthly P&I payment, every month. The component of the borrower’s periodic mortgage payment that collects for escrow items is referred to as the Taxes and Insurance (T&I) payment. Together, the P&I and the T&I are referred to as the “PITI” which constitutes the borrower’s entire periodic payment due each month.

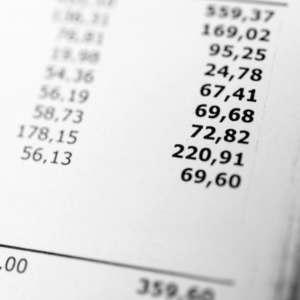

Let’s consider the following example. A mortgage servicer anticipates that a borrower’s real estate tax, due in September, will be $3,000. The servicer bases this anticipated amount on the tax amount paid the previous September. Additionally, this loan’s escrow account is analyzed annually in May. When the tax bill arrives in September, instead of the bill demanding $3,000, it demands $3,500 which the servicer pays, rendering the borrower’s escrow account short by $500. Additionally, and since the escrow account is only analyzed each May, the servicer continues to collect for a $3,000 tax bill even though it technically should be collecting for a $3,500 tax bill.

Upon analyzing a borrower’s escrow account, if a servicer determines that something for which it is responsible for paying on the borrower’s behalf increased resulting in an escrow shortage, the servicer will increase the borrower’s PITI payment to recover the amount paid in excess of what was anticipated in addition to adjusting for the higher real estate tax or insurance premium.

Returning to the previous example, when the escrow account is finally analyzed the following May, the borrower’s escrow account is identified as having a $1,000 shortage. This shortage is comprised of the $500 paid in excess of the amount anticipated plus $500 worth of monthly under collections ($41.67 x 12 = $500). Consequently, the lender increases the borrower’s T&I payment to recover the shortage in addition to raising the escrow payment in order to collect for the $3,500 tax amount anticipated for the following September.

By understanding how processes such as escrow accounts and their analyzations function, mortgage loan originators are better equipped to ensure that their borrowers understand the process in which they are engaged and don’t have to simply take their loan originator’s word for it. Customers who understand are more likely to enjoy their mortgage origination experience than those who don’t and will be far likelier to refer others back to that mortgage loan originator as well as return with future mortgage needs.